We sat down with DSR associate professor and director of the History of Religions program at UTM Kyle Smith to talk about his new book, Cult of the Dead: A Brief History of Christianity, which tells the fascinating story of how the world’s most widespread religion is steeped in the memory of its martyrs.

How did you come to write Cult of the Dead, a book for a general audience, rather than a more traditional academic text?

A lot of people have heard of “the early Christian martyrs.” But there’s this general tendency to think about them as the victims of a relatively brief episode in the past, an era of persecution in Roman antiquity that lasted for a while and then ended.

I wanted to show how the martyrs were never confined to the past but in many ways still are always at the centre of the story around which the whole history of Christianity revolves. The saints have long been understood as leading a sort of double existence: they’re in heaven, but they continue to intercede on Earth for the benefit of those who venerate them.

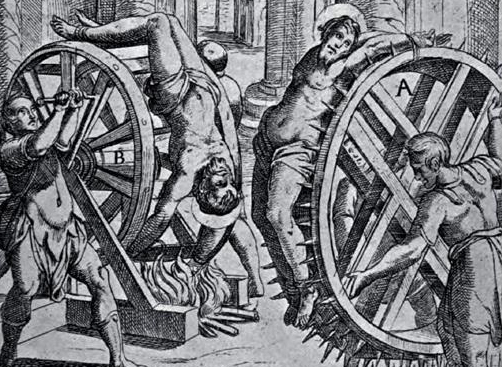

What inspired me to write this story for a general audience was a reprint I encountered of a sixteenth-century study of the various tools of torture by which Christians were supposedly killed. The author, a Catholic priest named Antonio Gallonio, was attempting to organise the saints according to the methods by which they were killed, so he begins with people who were killed on crosses or stakes or other sorts of devices on which you might be hung, and then he moves on to chopping or sawing devices, different sorts of pulleys and wheels, and so on. He's being a good, early modern scientist, classifying, dividing, and subdividing, but his goal was sectarian: he wanted to help the Catholics to whom he was writing better understand the suffering of their heroes who had been dead for well over a millennium.

Gallonio’s book shows how important the martyrs still were to Christians many centuries later and made me want to explain for a wider audience how the martyrs have cast this incredibly long shadow over Christianity’s history.

What role does the idea of martyrdom play in the Christian narrative?

There's always been this claim that Christians are killed for their faith. And that's been put forward intentionally both as a way of showing how the martyrs imitate Christ, who’s the prototypical martyr, but also as a way of challenging power—despite the fact that Christians themselves have been the ones in power in many times and places.

The idea of the Roman Empire as a whole persecuting Christians throughout all of its sphere of influence until Constantine the Great came along in the 4th century and converted to Christianity is a complete myth. Persecutions did happen, but for the most part the violence was limited, sporadic, and localized. Some Christians were killed, it’s true, but it’s not like the Romans were systematically hunting down and killing thousands of people—although the many stories of martyrs and their enduring popularity does sometimes make it seem that way. But I deliberately avoid the “so are these stories true or not?” sorts of questions. What I’m interested in is the persistence of the stories themselves. The point of the book is to show how the martyrs—through their stories, their relics, their shrines, their annual feast days on the calendar, and so on—are the true centrepiece of Christian culture.

Is persecution something that Christianity focuses on in a way that other religions don’t?

Claims about being persecuted aren’t unique to Christianity, of course, but I would say that there does seem to be something particularly acute about it with Christianity, even up to the present. Take Fox News and its wall-to-wall fear mongering about how secular liberals and global elites are coming to take away your God and your guns.

This persistent theme of “we're being persecuted” goes way back. My point is to say, “OK, so if there is this constant discourse about persecution and martyrdom—which is undeniable—then how has that shaped Christian culture up to and even well beyond the Protestant Reformation?”

Why is it that physical suffering seems to be so important?

Think about like this: the fundamental claim of Christianity is that God became human in a particular time and place. Jesus, in other words, had a body. Though it’s true that several early Christian group argued that that made no sense—and couldn’t get past the paradox of how God could become human—what became the orthodox opinion insisted that God had to assume human flesh for humanity itself to be saved. In this understanding, Jesus wasn’t just some animatron controlled by God, he was God, the son of God, who suffered, died, and was buried as we hear in the Nicene Creed. So this idea of a salvific sacrifice is crucial. I mean, it’s the key idea of Christianity! And for many early Christians it was something they thought they were called to imitate. It wasn’t enough to just live a pious life; the death of Christ had to be imitated too. Obviously, it’s a little more complex than that, but that’s the basic idea informing Christian martyrdom and the importance of physical suffering.

It shouldn’t be that hard to understand the cult of saints’ relics. All of us are still deeply interested in the things that are associated with our heroes.

Even after your live body isn't there any longer, there is still a very evident concentration on the physicality of things. It seems like Christianity tends to focus on the material, on relics – the objects associated with specific people.

For sure. During the Enlightenment era in the 18th century—and I’m thinking here of people like Edward Gibbon, who wrote The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire—people were disgusted with the idea that somebody might undertake a pilgrimage to go venerate a saint’s bone. That parallels earlier Roman thinking: fragmenting and distributing body parts and upholding them as holy objects was baffling to them. It probably is for many people today too.

But one of points I make in the book is that it shouldn’t be that hard to understand the cult of saints’ relics. All of us are still deeply interested in the things that are associated with our heroes. Go on eBay: how many thousands of dollars is a jacket that David Bowie once wore? Of course, it’s not the jacket that’s valuable, it’s that Bowie once wore it. Saints’ relics—whether you’re talking about a piece of bone, which makes us squeamish, or some piece of clothing they might’ve worn—aren’t that different. We put a lot of value on the things that belonged to our heroes. Relics aren't all that weird when you think of them that way.

You discuss in Cult of the Dead the way in which saints’ stories might morph in ways that reflected the anxieties of a particular period. How might that look?

A key example is how Saint Sebastian became the quintessential plague saint, the one to whom you’d pray for protection during times of epidemic disease. Sebastian might be familiar to many, as he is usually depicted as a martyr who was tied to a tree and shot through with arrows. There’s nothing in the ancient story about him that has anything to do with the plague, but many centuries after Sebastian’s death, the focus became these arrows and on Sebastian as a sort of lightning rod for God's anger. The bubo—the swollen lymph node caused by the plague—was likened to the wound of a dart, so many Christians developed this idea of Sebastian, this martyr riddled with arrows, as someone who could absorb the anger of God. You can see the roots of the flagellants here too, as they shared that idea. If you're intentionally afflicting yourself with something very painful as a means of penance, then maybe God will spare you the deadly dart of the plague.

Do you see anything happening in the current pandemic predicament that reflects that process of seeing stories through the lens of the era? We have a number of existential crises piling up on us it seems.

Writing this book during COVID-19 definitely affected how I thought about it. It was so interesting to look at medical texts from the 14th century, with doctors across Europe, both Christian and Muslim, trying to explain why the Black Death had arisen. On the one hand, it was divine anger, but there were also terrestrial explanations, like earthquakes in distant lands belching up sulfurous vapours that got spread by winds, causing bad air. To counter that, doctors of the era advised burning fragrant wood in your home or keeping lemons and violets nearby. Everybody wanted an explanation for all the death around them, and there really was a tension between natural and supernatural explanations for both the cause of the plague and how best to prevent it. I guess “bad air” is back again, but instead of lemons and violets we’ve got masks and HEPA filters.